Crowning of Charlemagne

by James Tillman

There are perhaps but two views of the state's purpose. In the traditional view, the state helps men to some definite idea of perfection by inculcating virtue in them through good laws; such an ideal has been advanced by Aristotle, Aquinas, and various Popes. In the classical liberal view, the state allows men to pursue whatever they want by protecting their freedom of action; such an idea has been advanced by Locke and various Protestants.

The dispute between the two has nevertheless crept into Catholic circles, despite the church's historical preference for the traditional view of the state's purpose. In the middle of the previous century, for instance, American Catholics saw the conflict between John Courtney Murray, who through the American experiment in religious liberty to be a good thing, and the Roman Catholic Curia, which did not and which therefore silenced him. Later in the century, Frank Meyer, convert from Communism to secular conservatism, argued with Brent Bozell, convert to Catholicism and founder of the militant Catholic magazine Triumph, over whether government's ultimate end is promoting freedom or promoting virtue. Other modern Catholic figures have tried to reconcile the Church's teaching with principles amenable to the American mind. Notwithstanding the accusation that they reconcile only inasmuch as they obscure, such arguments have had a great deal of success.

It is not the purpose of this article to address these arguments.

Rather, it is to question a premise upon which the arguments have been based. For the argument over whether the state should promote some specific morality is founded upon the conviction that the state is able to not promote some specific morality. Agreement over the descriptive, therefore, founds disagreement over the prescriptive. I would like to question this agreement. I will argue that the state, in the course of its actual operation, must ultimately promote some specific idea of morality -- whether a secular ideal, a Protestant ideal, and Islamic ideal, or a Catholic ideal. It is impossible for it not to do so. Thus, debating whether the state ought to move men to a specific end is foolish: the state will do so, whether one wants it to do so or not. The question is only what sort of morality the state will promote.

This thesis may be very counter-intuitive; surely, most Americans will wish to plead, government is able simply to step back from issues of morality, religion, and man's final end? Why must these issues come into the laws in some way? More specifically, why cannot government simply limit itself to the protection of human rights, such as the right to life, liberty, and property?

If government does not pass laws to bring man to his good, government must aim laws at something else. In the classical liberal scheme, government passes laws meant to protect man's rights. The idea of secular government is therefore founded on both the existence of such rights and the enforceability of such rights by the government. The former is a very dubious proposition -- indeed, if rights do exist they would certainly seem not to be morally neutral things. In their modern form, rights historically sprang into being from anti-Catholic sources, as in the French Revolution's Declaration of the Rights of Man. But for now I will pass over whether rights exist and whether they are morally neutral and examine instead how these rights would be defended by a government that recognizes their existence.

Rights are meant to delimit a sphere of action, within which each individual may do what he wants and the bordrs of which government is supposed to protect. Under such a system, government does not look to whether property is used for good or for ill; it simply protects one's right to have it and use it. Government does not look to whether free speech spreads lies or truth; it simply protects one's ability/right to speak. Deliberation regarding laws centers on how best to protect the various rights, not onl whether laws will help men be better men. Like that of the Wiccans, the classical liberal motto is "If it harm none, do what ye will."

Everyone assaults everyone else with cries of intolerance. And everyone is right; everyone is intolerant. There can be no peace between those with different moralities, different ideas of human nature, and different ideas of God; the ideal of government as a neutral umpire has never existed and never can exist.

* * * * * * *

When such rights are examined, we find quickly that they are not absolute. Freedom of speech infamously does not give one the right to yell "Fire!" in a crowded theatre. Neither does it give one the right to put a sign on one's lawn advocating the lynching of African-Americans. The right to freedom of speech is outweighed by the right to life. The majority of cases, however, are not so clear. Does freedom of speech permit me to sell books advocating a subversive and Communist political philosophy? Does it permit me to sell books on how to conduct a coup d'état? Does it permit one to put up billboards quoting the Levitical laws against sodomy? Such cases are not easy to decide and will require significant prudential deliberation regarding the goods to be gained and lost by each course of action. In each case the so-called "right" to freedom of speech is clearly not an absolute right; those who make decisions do not make them based upon clear and unambiguous laws, but upon prudential weighing of the various goods involved.

Similarly, the right to freedom of religion requires prudential decision-making. Some religions involve smoking marijuana; others involve polygamy; others involve the execution of those who decide to leave that religion and the establishment of a world-wide theocracy beneath religious law. Such religions may be offensive to Catholics, just as the Catholic religion is offensive to those who believe that it teaches people to hate homosexuals, that it represses man's natural instincts, that it advocates the subjugation of women, or that it leaves one ultimately loyal to a monarch in the Vatican rather than to the United States. When government decides what sort of religion to allow and to what extent to allow it, then it does not simply take into account the right to religious freedom; one also takes into account a host of other moral evaluations regarding the importance of various goods. Similar instances might be given as regards education, the right to private property, and so on and so forth.

Pope Leo XIII

* * * * * * *

The Popes in the nineteenth and early twentieth century tried to keep men from giving up the fight for Christ's social reign, but their efforts failed. The secular state triumphed, in which a secular, humanistic morality is used as a basis for the laws, in which the Church is marginalized and forced to conform to rules that effectively muzzle and tame it, and in which men's loyalties are but nominally to the church and really for their government or careers.

* * * * * * *

Thus, in all cases the so-called rights to which people appeal are not absolute guidelines for government; they are simply things often considered good, which must be weighed and curbed when they interfere with other good things. Is freedom of speech more important than the harm caused by racism? Is it more important than the offense caused by Christian teaching on homosexuality? Is it more important thatn the injury to the innocence of children caused by indecent advertisements? Such decisions cannot be rationally evaluated unless one appeals to a specific, concrete, moral ideal; and so, the decisions and actions of government cannot be rationally evaluated unless one appeals to a specific, concrete, moral ideal; and so, the decisions and actions of government cannot be morally neutral. Whether those in government think religion to be important, think Catholicism to be true, think the family to be important, or think a thousand other things will alter their decisions as they weigh all the various variables involved in deciding upon a specific course of action. Government's action must therefore always favor one moral scheme above another.

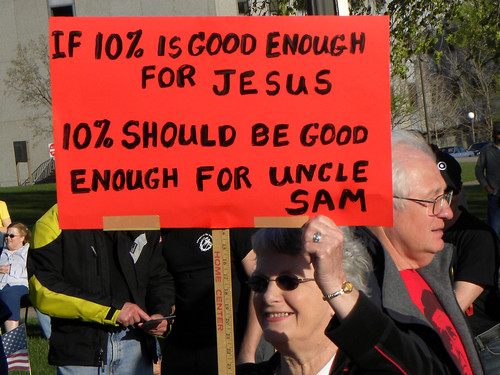

Nor is it simply in controversial, high-profile issues that government must take into account various moral ideals. Consider tax laws. Government often taxes corporations at lower rates than it taxes the family; furthermore, corporations are generally taxed on the profits that they make -- on their sales minus expenses -- rather than simply on gross income. On the other hand, families are taxed on gross income without regard for the expenses the family incurs. Such laws favor the production of stuff rather than the production and raising of children; and while both are necessary to the economy, each is necessary in different ways and to different degrees. One might argue that the government's policy is just or is unjust, but in any event such argument would probably refer to the relative importance of the family and the corporation, the benefits of small-scale versus large-scale production, distributism and capitalism, and other moral issues. Even the blandest of governmental decisions, therefore, involve moral evaluation.

Consider, again, the government and the mandatory education of children. Few would disagree that children ought to be educated. Yet evaluating whether the government should mandate some sort of education and what the content of that mandated education should be; whether the government provide public schools and what the curricula of such schools should be is anything but a morally neutral affair: it involves one's idea of the relation of parents to children, the permanence and role of the family, the relative importance of the family and government, and even the differential treatment of men and women in society. To act on such an issue is to give an opinion on it: to mandate the public education of children unless parents meet certain stringent governmental requirements, for instance, is to rule that children are in some ways more the responsibility of government than of parents -- and thus that government ought to have more control over them. A morally neutral argument can be nothing but a farce under such circumstances.

The impossibility of governmental neutrality contributes to the often shrill accusations of bigotry flung from side to side in the current day. Homosexual activists accuse Christians of trying to impose their morality on others; Christians accuse homosexuals of trying to impose their views on school children; television advertisers accuse Christians of censorship while Christians accuse them of corrupting the youth; everyone assaults everyone else with cries of intolerance. And everyone is right; everyone is intolerant. There can be no peace between those with different moralities, different ideas of human nature, and different ideas of God; the ideal of government as a neutral umpire has never existed and never can exist. The classical liberal ideal of a government indifferent to man's final end seemed possible only because of the mostly Christian consensus found in the first liberal governments; the cracks cause by disagreement were few and far between and easily disguised. Yet centuries of secularity have done their work, and religious pluralism has introduced beliefs yet more and more divergent. The façade can no longer be maintained. The state cannot be neutral: one's own moral system must reign in it, or one will be crushed by that of another.

Inasmuch as the Republican -- or even the Democrat -- agenda agrees witht he Catholic, to that extent they can be made temporary allies; but we must never mistake such an alliance for a friendship. There is no agenda for the Catholic but the Catholic agenda ...

* * * * * * *

In light of this fact one must applaud the wisdom of the Church, which condemned the ideas of liberalism from its start. The Syllabus of Errors of Blessed Pius IX condemns the idea that "the Church ought to be separated from the State, and the State from the Church"; it condemns the idea that "in the present day it is no longer expedient that the Catholic religion should be held as the only religion of the State, to the exclusion of all other forms of worship." When one ceases trying to wrench society towards a state in which God and His rule is recognized, society must slide towards a denial of God and His rule. The Popes in the nineteenth and early twentieth century tried to keep men from giving up the fight for Christ's social reign, but their efforts failed. The secular state triumphed, in which a secular, humanistic morality is used as a basis for the laws, in which the Church is marginalized and forced to conform to rules that effectively muzzle and tame it, and in which men's loyalties are but nominally to the church and really for their government or careers.

The current political spectrum distorts this necessary conflict; it causes us to pretend that it can be sidestepped. Members of the Republican Party and members of the current Tea Party cry for government to cease its crawling -- and occasionally sprinting -- socializing of medicine and business, and inasmuch as they do so they are good. But will they admit that education cannot be neutral, and that our current concept of government-run education is flawed? Will they admit that the right to private property includes no right to sell products that help destroy family and society? Will they admit the principle of subsidiarity and admit that local communities need their power increased greatly, just as the federal and state governments must be shrunk? Inasmuch as the Republican -- or even the Democrat -- agenda agrees witht he Catholic, to that extent they can be made temporary allies; but we must never mistake such an alliance for a friendship. There is no agenda for the Catholic but the Catholic agenda, which would require decades of unremitting effort for its realization and which would require men to transcend most of the issues currently dividing political parties. The Catholic agenda requires us to admit what the rest of society yet hypocritically denies -- that between rival moral theories there can be no peace.

Catacombs or Christendom? Society slides and wavers between the two; but there can be no third way.

[James Tillman is a Catholic Journalist and graduate of Christendom College. The present article, "An Apology for the Confessional State," was originally published in The Latin Mass: A Journal of Catholic Culture and Tradition, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Winter 2011), pp. 60-63, and is reprinted here by kind permission of Latin Mass Magazine, 391 E. Virginia Terrace, Santa Paula, CA 93060.]