The basic question, of course, centers on the authority to define canonicity. The question of pseudonymity that he treats in his second post is a secondary detail, and I won't address it here. Rather, I wish to comment briefly on the question of circular reasoning that he raises in his second post.

The basic question, of course, centers on the authority to define canonicity. The question of pseudonymity that he treats in his second post is a secondary detail, and I won't address it here. Rather, I wish to comment briefly on the question of circular reasoning that he raises in his second post.First, the claim is sometimes made that the Catholic Church is circular in appealing to Scripture to support her authority and then claiming the final say in how to interpret Scripture. But there is no circularity here, first, because she does not claim sola scriptura; and, second, because if she has the authority she claims, the case is no different logically from that of the NT writers appealing to the Old Testament (OT) for support while claiming divine warrant for their NT interpretations.

Second, others suggest that the Church's position is circular because it boils down to saying: "we must believe Rome because Rome says so." The concern here for avoiding self-serving abuses by those in authority is legitimate, but misplaced. The Catholic is not asked to submit to the Church because the Church says so, but because Catholics understand God to have appointed the Church and her lawfully ordained leaders as administrators of His commission. The Church is subject to the Word of God (including the message of the Bible), even while she guardian and master (as Magisterium) of the Bible's text and interpretation. The Vatican II document, Dei verbum, declares that the "Magisterium is not superior to the Word of God, but is its servant" (ch. 2, sec. 10, p. 756). The Church's authority is not an "enabling" one but a "restraining" one, which prevents any reigning Pope from arbitrarily inventing heretical new doctrines by binding him to an infallible tradition (including Scripture) traceable to the "apostolic deposit of faith."

The wording of Pope John Paul II's Apostolic Letter reserving priestly ordination to men alone, Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, is instructive in this regard: he says, quoting Pope Paul VI, that the Church "does not consider herself authorized to admit women to priestly ordination" (emphasis added). Again, Peter Kreeft also remarks in an article entitled "Gender and the Will of God," Crisis magazine (Sept. 1993): "The Catholic Church claims less authority than any other Christian church in the world; that is why she is so conservative. Protestant churches feel free to change 'the deposit of faith' ... or of morals (e.g. by allowing divorce, though Christ forbade it), or of worship" (20).

Third, still others claim that Catholicism is circular because it bases our conviction of the Bible's inspiration on the Church's infallibility and the Church's infallibility on the word of an inspired Bible. But it does not. While it may appeal to the Church's infallible teaching in support of our conviction that Scripture is inspired, it does not have to argue for the Church's infallibility from the Bible alone. It can argue this from other sources of early Church tradition as well. Hence there is no logical circularity here.

Fourth, there is a larger sense in which circularity, as Pontificator suggests, cannot be avoided in arguing for the ultimate criterion of a system. This is what Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas meant by saying that first principles are indemonstrable. Why should one be logical? Because it would be illogical not to be! Why should one believe God's Word? Because it is the Word of God, of course! Every system is based on presuppositions that control its epistemology, argument, and use of evidence; therefore ultimate circularity is philosophically inescapable. But this does not mean that circularity is permissible in other (penultimate) sorts of arguments. "The Bible is inspired because the Bible says its inspired" is a circular argument whose circularity is not justified. It lacks cogency. A document's self-attestation is insufficient warrant for accepting its claims. The argument can gain cogency only by enlarging its circle to include also the attestation of the Church and data of sacred and secular history. By contrast, "The Bible means what the Church says it means" is not circular in this way, since the Church's interpretation is not closed off from history, but empirically testable for fidelity and coherence both against Scripture and the other traditions of the Church.

Related reading:

- Al Kimel, "Did the Church "create" the Scripture?" (Pontificator)

- Philip Blosser, comment: Did the Church "create" Scripture? (Scripture and Catholic Tradition)

- Al Kimel, "Canon to the right of them; canon to the left of them"

- Philip Blosser, comment: "The question of authority in relation to the biblical canon"

- Al Kimel, "Canon in front of them, rode the six hundred"

- Philip Blosser, comment: "Canonicity and the problem of circular reasoning."

Al Kimel, at

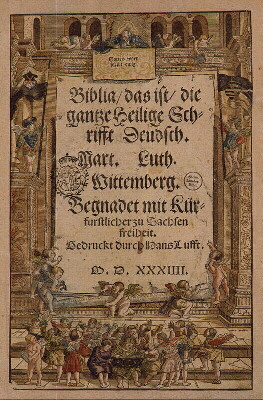

Al Kimel, at  I know they taught that at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia when I attended there in the seventies. Like all those other ultimately subjectivist criteria (the "inner promptings of the Holy Spirit," "what preaches Christ," etc.), it ends up functioning as a wax nose that can be turned in nearly any direction the interpreter desires. Luther would have left out Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation, which Luther classified in the first edition of his Deutche Bibel (pictured left) as non-canonical books, along with the Deuterocanonicals. Most Protestants today would be rightly scandalized by a Bible that omitted Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation. The one thing you didn't address is the bizarre fact that most Protestants do, however, omit the Deuterocanonical books without batting an eye. I say "bizarre" because they typically cite St. Athanasius' Easter encyclical of AD 367 as the first public record of the complete list of the twenty-seven books of the New Testament--as does the popular evangelical textbook by Walter A. Elwell and Robert W. Yarbrough, Encountering the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p. 27--without batting an eye, either ignoring or ignorant of the fact that the same Athanasian list includes all of the Deuterocanonicals as well. It does them no help to cite the canon of ecclesiastical consensus at this point, because the consensus clearly recognized the Deuterocanonicals as Scripture.

I know they taught that at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia when I attended there in the seventies. Like all those other ultimately subjectivist criteria (the "inner promptings of the Holy Spirit," "what preaches Christ," etc.), it ends up functioning as a wax nose that can be turned in nearly any direction the interpreter desires. Luther would have left out Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation, which Luther classified in the first edition of his Deutche Bibel (pictured left) as non-canonical books, along with the Deuterocanonicals. Most Protestants today would be rightly scandalized by a Bible that omitted Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation. The one thing you didn't address is the bizarre fact that most Protestants do, however, omit the Deuterocanonical books without batting an eye. I say "bizarre" because they typically cite St. Athanasius' Easter encyclical of AD 367 as the first public record of the complete list of the twenty-seven books of the New Testament--as does the popular evangelical textbook by Walter A. Elwell and Robert W. Yarbrough, Encountering the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), p. 27--without batting an eye, either ignoring or ignorant of the fact that the same Athanasian list includes all of the Deuterocanonicals as well. It does them no help to cite the canon of ecclesiastical consensus at this point, because the consensus clearly recognized the Deuterocanonicals as Scripture.  Greek was the lingua franca of the New Testament ethos, and the "Scripture" to which St. Paul referred in II Tim. 3:16 as "inspired," and the "Scripture" to which other NT writers quoted and cited in their epistles and gospels was for all practical purposes the Septuagint (LXX), which included the Deuterocanonicals. I think it's the Nestle-Alland edition of the Greek NT that contains the appendix listing the multitude of allusions in the NT to the Deuterocanonical books (worth checking out). Also every listing of the canonical books of the Bible in the Council of Rome (AD 382), Council of Carthage (AD 397), St. Innocent (405), and Council of Trent (AD 1546) includes all of the Deuterocanonicals, even though they are called by slightly different names (

Greek was the lingua franca of the New Testament ethos, and the "Scripture" to which St. Paul referred in II Tim. 3:16 as "inspired," and the "Scripture" to which other NT writers quoted and cited in their epistles and gospels was for all practical purposes the Septuagint (LXX), which included the Deuterocanonicals. I think it's the Nestle-Alland edition of the Greek NT that contains the appendix listing the multitude of allusions in the NT to the Deuterocanonical books (worth checking out). Also every listing of the canonical books of the Bible in the Council of Rome (AD 382), Council of Carthage (AD 397), St. Innocent (405), and Council of Trent (AD 1546) includes all of the Deuterocanonicals, even though they are called by slightly different names (