The problem with

Hans Kung is that, like the rest of that part of the post-Christian world that has been reluctant to let go of its sentimental attachment to Christianity, he wants to change the meaning of Christianity to conform to his post-Christian commitments rather than to admit that his beliefs are no longer, in any traditionally recognizable sense of the term, Christian. In short, Kung wants to belong to the historical Christian community without accepting key historical Christian beliefs. This is amply clear, once again, from his recently published autobiography,

My Struggle for Freedom: Memoirs [Amazon link], in which he replays his old lamentations about the Vatican's "authoritarian repression" of his academic freedom to teach whatever he wants, even if the Church may consider it heretical, and its denial of his canonical right to present himself to the public as a Catholic theologian. He reminds me, in a way, of the members of the original British Humanist Association, all of them atheists, who used to gather in one of their homes to sing traditional Christian hymns for their sentimental value--a phenomenon not altogether different from the annual Christmas albums put out by entertainers not otherwise known for their piety.

Kung was born in 1928 and educated during the heyday of Protestant Liberalism, when that lovely legacy of the Enlightenment, the acids of the rationalistic historical-criticism of the Bible, were eating out the heart of mainline Protestant denominations.

He was one of those Catholics who had already been drinking deeply at those contaminated Protestant fonts of biblical scholarship before the Second Vatican Council seemed to permissively fling open the doors of the Church to the world of non-Catholic scholarship. It is understandable, then, how he must have looked eagerly for Vatican II to sanction a revisioning of the Catholic Faith along lines that he saw as reasonable from his own studies of secular Protestant sources. His

Justification: The Doctrine of Karl Barth and a Catholic Reflection [Amazon link] (1964) shows that he was already interested in drawing converging lines between Catholic and the secularized Protestant theologian,

Karl Barth (pictured below right). I realize that many Christians, both Catholic and Protestant, hold Barth in high esteem, viewing him as a champion of "Neo-Orthodoxy" in contrast to the "Liberalism" of demythologizing thinkers such as

Rudolf Bultmann, and I realize that they might find my labeling of him as a "secular Proestant" offensive. Yet I make my remarks advisedly.

Barth is deceptive. He writes and talks as if he believes in the traditional Christian doctrines. But he doesn't. As University of Edinburgh Professor J.C. O'Neill writes in his chapter on Barth in

The Bible's Authority [Amazon link] (1991):

Barth begins from from the starting-point that none of the miracles in the Bible actually happened .... Opponents of Barth like Bultmann were infuriated by Barth's seeming to say that he believed that the resurrection happened (in the normal sense, by which he grave became empty and the transformed body of Jesus left this universe) when he did not believe anything of the sort--but Barth never really concealed his actual position from those who took care to read carefully what he wrote. (p. 273)

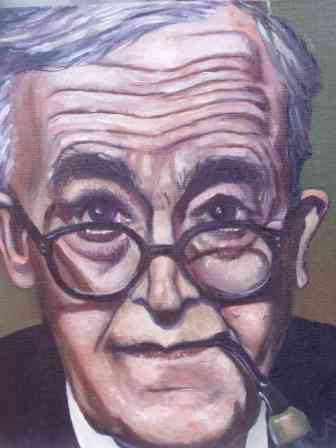

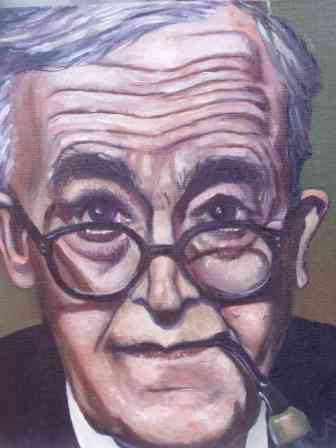

While other Protestant theologians, like

Paul Tillich (pictured left), clearly distinguish when they're writing "devotionally" (when they sound like evangelical Christians) and when they're writing "scholarly" (when they sound like atheists), Barth is more subtle and requires greater discernment. Many of these Protestants continued to employ a Christian vocabulary while investing their terms with demythologized post-Christian meanings. Hans Kung is one of the numerous fatalities resulting from this historical development.

A sampling of Kung's publishing record is telling.

The Church [Amazon link] (1967) offered several corrosive revisionings of the traditional understaning of the Church.

Apostolic Succession: Rethinking a Barrier to Unity [Amazon link], an edited anthology (1968), shows ecumenical sympathies being enlisted in the less-than clandestine service of further revisionism.

Infallible?: An Inquiry (1971), later reissued as

Infallible?: An Unresolved Enquiry [Amazon link] (1994), continued Kung's crusade of dissent.

On Being a Christian [Amazon link] (1979), offered a denaturing "up-dating" of Christian belief from the standpoint of modern secularist concerns, including an uncritical acceptance of radical historical-critical biblical interpretations and "demythologizations" of traditional doctrines. For example, the crucifixion "becomes an appeal to renounce a life steeped in selfishness." Lovely: the Passion of the Christ can be reduced to the message of Barney and Friends.

The same year, on December 18, 1979, the Vatican curia (finally!) issued a declaration against Kung's doctrinal views, withdrawing his canonical mission to teach Catholic theology, although his academic tenure was protected by the University of Tubingen. Kung, though stripped of his canonical

mandatum as a Catholic theologian, continued his attack on the Church undaunted. In 1981 he published

Does God Exist?: An Answer for Today [Amazon link]--a bizarre discussion in which he continues to affirm that, yes, God does exist, even though Jesus never existed, Noah's flood never occurred, the story of Exodus is a myth, the universe has always existed and has no need for a creator, and the Bible is a morass of contradictions, and he provisionally accepts a feminist notion about a "goddess" and primitive matriarchy.

The Church in Anguish: Has the Vatican Betrayed the Council? [Amazon link], an anthology edited with Leonard Swidler (1997), exhibits Kungs hostility to the Vatican's insistance that Vatican II was never intended as a rupture with Catholic Sacred Tradition.

Why I Am Still a Christian [Amazon link] (1986) offers a personal rationale for why Kung still wants to be identified as a Christian and a Catholic despite the fact that he's not, and despite his vociferous renunciation of Rome's authority, which he commonly refers to as the "Roman Kremlin."

Recently Hans Kung was interviewed by Stephen Crittenden for The Religion Report on Radio National (December 15, 2004). The interview, "

A conversation with Number 399/57 i" is named after the file number that Kung keeps for life in the offices of the Inquisition, or Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

In the interview, Kung describes his personal acquaintance with the popes since Pius II, and calls John Paul II a man of "the mediaeval, anti-reformation, anti-modern paradigm of the church." Remarks such as these must be understood on some level as grandstanding, since otherwise they would be nearly unintelligible. No pope, after all, has done more to address contemporary concerns centering on the subjective experiential dimension of the lived experience of the believer than Karol Wojtyla, the student of phenomenology, author of

The Acting Person [Amazon link],

The Theology of the Body According to John Paul II: Human Love in the Divine Plan [Amazon link],

Love and Responsibility [Amazon link], the philosopher who wrote two dissertations (one in philosophy on

Max Scheler, the other in theology on

St. John of the Cross) and went on to become Pope John Paul II. Kung is not stupid. He knows this. But what irks him is that the Pope does all of this without in any way intending to compromise the objective authority and integrity of the dogmatic constitution of the Catholic Faith. This is what Kung cannot stand. Kung wants the personalism and subjective focus on experience without the authority of objectively binding dogma; but the latter is what keeps John Paul's (objectively grounded) subjective personalism from becoming Kung's (historically relativistic) personal subjectivism.

Prominent in the interview is Kung's admiration for the aforementioned Karl Barth, along with some grandstanding scare tactics refencing Opus Dei. He says:

The next [papal] election will certainly be very decisive, and there is no doubt that especially all these Cardinals from the  Opus Dei, who are favourable for this secret organisation which is an authoritarian, Spanish organisation [... is he playing to the hype over Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code here? ...] which has a great influence and which was supported heavily already by Karol Wojtyla when he was Archbishop of Krakow. And the whole question will be: will now the Catholic church be dominated again by a clique of people who is in this authoritarian organisation which is, as a matter of fact, living in a mentality of, I would say, the counter-Reformation, of anti-Modernism, or will we have enough bishops who still remember the Second Vatican Council and who see especially the terrible situation in which our church is in, in the present moment?

Opus Dei, who are favourable for this secret organisation which is an authoritarian, Spanish organisation [... is he playing to the hype over Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code here? ...] which has a great influence and which was supported heavily already by Karol Wojtyla when he was Archbishop of Krakow. And the whole question will be: will now the Catholic church be dominated again by a clique of people who is in this authoritarian organisation which is, as a matter of fact, living in a mentality of, I would say, the counter-Reformation, of anti-Modernism, or will we have enough bishops who still remember the Second Vatican Council and who see especially the terrible situation in which our church is in, in the present moment?

What is even more remarkable is how Kung immediately goes on to characterize this "terrible situation in which our church is in, in the present moment":

If you see for instance that the Church of Ireland -- I know that a lot of bishops and priests in Australia too, come from this beautiful and most constructive Ireland -- I mean constructive in a way that they constructed a great deal of churches, especially in the Anglo Saxon world, and I admire very greatly these people, I was often there. But it's terrible to see what happens to a Catholic country like Ireland, that this country, who was practically sending priests, hundreds and thousands of priests all over the world, they are practically lost now. They had in 1990, they still had 300 ordinations a year. Last year they had eight ordinations. Eight! As a matter of fact, also in other European countries, and this will happen also to other parts of the world, I'm sure also in Australia, practically the celibate clergy is dying out. And we have already in our German speaking countries, more or less half of the parishes who have not anymore a pastor. We are losing the Sunday Eucharist, all because we do not want to have ordained married men, and why we don't want to have ordained women.

So the reason for the vocational crisis and plummeting Mass attendance in Ireland and Germany, according to Kung, is

all because we do not want to have ordained married men or ordained women--when, in fact, it is the

disbelief underlying such attitudes of revisionism and dissent that have rendered the Catholic populations of these countries indifferent to priestly vocations and Mass attendance!

Again, when asked his opinion of the present pontificate, Kung responded:

I would agree that [John Paul II has] preached the gospel for the poor, he was for human rights in the world. But all this was in blatant contradiction with what he has done in his own church, because he repressed human rights in the church, he repressed the rights of theologians and he reintroduced the Inquisition, he offended very often women because of his Marian piety, exalting the Virgin Mary as an example, and repressing women in the church discipline.

The fact that Kung sees a "contradiction" between the Pope's social teaching and his other teaching reveals Kung's secular commitments, because there is simply no contradiction at all when the matter is viewed from within the perspective of traditional Church teaching itself. Because the secular vantage point is inevitably superficial, it can easily misconstrue the Pope's affirmation of the traditional Catholic veneration of Mary as contradicting his affirmation of the traditional Catholic prohibition of women priests. Likewise, the Pope's support for human rights and compassion for the poor may seem to contradict his willingness to allow the Church to censure theologians (like Kung) who dissent from Church teaching. Yet there is altogether no contradiction between these things when seen from within traditional Catholic understanding of the matter. The problem comes only with

unbelief: if one no longer

believes in an authoritative Revelation, preserved and proclaimed by the Church under the infallible guidance of the Holy Spirit, then everything caves in. There is no longer any objective basis for censuring views that dissent from traditional Catholic beliefs, because all beliefs are relative and subjective. The exclusion of women from ordained ministry then becomes no more than a long standing arbitrary and unjust convention of the Church; and one might as well lobby for the elevation of Mary into a "goddess" as to maintain that God is a triune Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

What is evident throughout the interview is Kung's unrelentingly secular--that is to say, immanent, naturalistic (anti-supernaturalistic) viewpoint. This is particularly evident in his discussion of the pope's charism of infallibility. But I have discussed enough of Kung. He has done his share of damage over the past two generations. I am only too pleased that I did not waste much of my time as a student reading his books. My prayer is that others would not waste their time on him either, and, still more, that they would not be taken in by his misleadingly sophistical, tired reformulations of the failed and secularized Protestant/Enlightenment project.

One of the best examples of a powerful antedote to this kind of foolishness is a little essay by C.S. Lewis entitled "Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism," which is available in a collection of essays by Lewis entitled Christian Reflections [Amazon link] (1967; reprinted by Eerdmans, 1994). The following are some excerpts from Lewis' essay, which begins on p. 152 and contains four objections (or "bleats") about modern New Testament scholarship:

One of the best examples of a powerful antedote to this kind of foolishness is a little essay by C.S. Lewis entitled "Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism," which is available in a collection of essays by Lewis entitled Christian Reflections [Amazon link] (1967; reprinted by Eerdmans, 1994). The following are some excerpts from Lewis' essay, which begins on p. 152 and contains four objections (or "bleats") about modern New Testament scholarship:3. Thirdly, I find in these theologians a constant use of the principle that the miraculous does not occur... This is a purely philosophical question. Scholars, as scholars, speak on it with no more authority than anyone else. The canon 'if miraculous, unhistorical' is one they bring to their study of the texts, not one they have learned from it. If one is speaking of authority, the united authority of all the Biblical critics in the world counts here for nothing.

The problem with Hans Kung is that, like the rest of that part of the post-Christian world that has been reluctant to let go of its sentimental attachment to Christianity, he wants to change the meaning of Christianity to conform to his post-Christian commitments rather than to admit that his beliefs are no longer, in any traditionally recognizable sense of the term, Christian. In short, Kung wants to belong to the historical Christian community without accepting key historical Christian beliefs. This is amply clear, once again, from his recently published autobiography,

The problem with Hans Kung is that, like the rest of that part of the post-Christian world that has been reluctant to let go of its sentimental attachment to Christianity, he wants to change the meaning of Christianity to conform to his post-Christian commitments rather than to admit that his beliefs are no longer, in any traditionally recognizable sense of the term, Christian. In short, Kung wants to belong to the historical Christian community without accepting key historical Christian beliefs. This is amply clear, once again, from his recently published autobiography,  He was one of those Catholics who had already been drinking deeply at those contaminated Protestant fonts of biblical scholarship before the Second Vatican Council seemed to permissively fling open the doors of the Church to the world of non-Catholic scholarship. It is understandable, then, how he must have looked eagerly for Vatican II to sanction a revisioning of the Catholic Faith along lines that he saw as reasonable from his own studies of secular Protestant sources. His

He was one of those Catholics who had already been drinking deeply at those contaminated Protestant fonts of biblical scholarship before the Second Vatican Council seemed to permissively fling open the doors of the Church to the world of non-Catholic scholarship. It is understandable, then, how he must have looked eagerly for Vatican II to sanction a revisioning of the Catholic Faith along lines that he saw as reasonable from his own studies of secular Protestant sources. His  Barth is deceptive. He writes and talks as if he believes in the traditional Christian doctrines. But he doesn't. As University of Edinburgh Professor J.C. O'Neill writes in his chapter on Barth in

Barth is deceptive. He writes and talks as if he believes in the traditional Christian doctrines. But he doesn't. As University of Edinburgh Professor J.C. O'Neill writes in his chapter on Barth in  While other Protestant theologians, like Paul Tillich (pictured left), clearly distinguish when they're writing "devotionally" (when they sound like evangelical Christians) and when they're writing "scholarly" (when they sound like atheists), Barth is more subtle and requires greater discernment. Many of these Protestants continued to employ a Christian vocabulary while investing their terms with demythologized post-Christian meanings. Hans Kung is one of the numerous fatalities resulting from this historical development.

While other Protestant theologians, like Paul Tillich (pictured left), clearly distinguish when they're writing "devotionally" (when they sound like evangelical Christians) and when they're writing "scholarly" (when they sound like atheists), Barth is more subtle and requires greater discernment. Many of these Protestants continued to employ a Christian vocabulary while investing their terms with demythologized post-Christian meanings. Hans Kung is one of the numerous fatalities resulting from this historical development.

In the interview, Kung describes his personal acquaintance with the popes since Pius II, and calls John Paul II a man of "the mediaeval, anti-reformation, anti-modern paradigm of the church." Remarks such as these must be understood on some level as grandstanding, since otherwise they would be nearly unintelligible. No pope, after all, has done more to address contemporary concerns centering on the subjective experiential dimension of the lived experience of the believer than Karol Wojtyla, the student of phenomenology, author of

In the interview, Kung describes his personal acquaintance with the popes since Pius II, and calls John Paul II a man of "the mediaeval, anti-reformation, anti-modern paradigm of the church." Remarks such as these must be understood on some level as grandstanding, since otherwise they would be nearly unintelligible. No pope, after all, has done more to address contemporary concerns centering on the subjective experiential dimension of the lived experience of the believer than Karol Wojtyla, the student of phenomenology, author of  Opus Dei, who are favourable for this secret organisation which is an authoritarian, Spanish organisation [... is he playing to the

Opus Dei, who are favourable for this secret organisation which is an authoritarian, Spanish organisation [... is he playing to the  So the reason for the vocational crisis and plummeting Mass attendance in Ireland and Germany, according to Kung, is all because we do not want to have ordained married men or ordained women--when, in fact, it is the disbelief underlying such attitudes of revisionism and dissent that have rendered the Catholic populations of these countries indifferent to priestly vocations and Mass attendance!

So the reason for the vocational crisis and plummeting Mass attendance in Ireland and Germany, according to Kung, is all because we do not want to have ordained married men or ordained women--when, in fact, it is the disbelief underlying such attitudes of revisionism and dissent that have rendered the Catholic populations of these countries indifferent to priestly vocations and Mass attendance!

which relates the first meeting of Paul with Peter, as well as his later meeting with him. Imagine Paul, the most educated Jew in all Palestine-- the protoge of Rabbi Gamaliel, a Roman citizen, speaker of Latin and Greek as well as Hebrew and Aramaic, a Pharisee by training-- just imagine this Paul, converted independently on the road to Damascus, after three years going up to Jerusalem to submit himself to this head-strong and probably arrogant-seeming Joe Sixpack of a fisherman, PETER, accepting his authority as head of the Church!! A truckload to think about there.

which relates the first meeting of Paul with Peter, as well as his later meeting with him. Imagine Paul, the most educated Jew in all Palestine-- the protoge of Rabbi Gamaliel, a Roman citizen, speaker of Latin and Greek as well as Hebrew and Aramaic, a Pharisee by training-- just imagine this Paul, converted independently on the road to Damascus, after three years going up to Jerusalem to submit himself to this head-strong and probably arrogant-seeming Joe Sixpack of a fisherman, PETER, accepting his authority as head of the Church!! A truckload to think about there. One of the chief measures of being Catholic is one's willingness to submit himself to the Church as to Christ, believing those two things can't be separated in matters of faith and morals, doctrine and discipline. I can understand the subjective experience of emptiness in segments of one's spiritual pilgrimage. St. John of the Cross wrote about that in his

One of the chief measures of being Catholic is one's willingness to submit himself to the Church as to Christ, believing those two things can't be separated in matters of faith and morals, doctrine and discipline. I can understand the subjective experience of emptiness in segments of one's spiritual pilgrimage. St. John of the Cross wrote about that in his  That has to be excruciatingly painful in some respects. They say that Mother Teresa lacked, for the great majority of her career in Calcutta, any personal sense of reassurance about God's will in what she was doing. And yet nobody--least of all the famished and dying Indians she pulled out of the gutters of Calcutta--would have ever known this: she had to go from day-to-day on sheer faith. This, it seems to me, is what we're asked to do when the externals of our faith life don't seem to "deliver." This is certainly the case for me at the moment, at least when it comes to Sunday Masses. The music and such seem to detract, rather than assist, the ascent of the soul to God.

That has to be excruciatingly painful in some respects. They say that Mother Teresa lacked, for the great majority of her career in Calcutta, any personal sense of reassurance about God's will in what she was doing. And yet nobody--least of all the famished and dying Indians she pulled out of the gutters of Calcutta--would have ever known this: she had to go from day-to-day on sheer faith. This, it seems to me, is what we're asked to do when the externals of our faith life don't seem to "deliver." This is certainly the case for me at the moment, at least when it comes to Sunday Masses. The music and such seem to detract, rather than assist, the ascent of the soul to God.

Catholic in your family, and so forth. But if you could have a talk with your dear patron saint, St. Ambrose, do you not think he would say, "Dear friend, get to confession and get yourself back to church!"? Furthermore, as to your heretical opinions, do you not think he would tell you, "Dear daughter, do you imagine that Christ established the Church only to undermine it by having her teaching held hostage by the opinions of the masses? Of course everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but do you think that following your own opinions, any more than following one's conscience, can possibly guarantee that one will do the right thing? Have we not the obligation to submit our opinions to the governance of the Church, to let our consciences and opinions be informed by her teaching? What would happen to the Church if we let her path be determined by majority vote or by the public media? Perhaps that is preciesly what is wrong with your American Church these days ... "

Catholic in your family, and so forth. But if you could have a talk with your dear patron saint, St. Ambrose, do you not think he would say, "Dear friend, get to confession and get yourself back to church!"? Furthermore, as to your heretical opinions, do you not think he would tell you, "Dear daughter, do you imagine that Christ established the Church only to undermine it by having her teaching held hostage by the opinions of the masses? Of course everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but do you think that following your own opinions, any more than following one's conscience, can possibly guarantee that one will do the right thing? Have we not the obligation to submit our opinions to the governance of the Church, to let our consciences and opinions be informed by her teaching? What would happen to the Church if we let her path be determined by majority vote or by the public media? Perhaps that is preciesly what is wrong with your American Church these days ... "

One can feel as if God is smiling upon him when he is embarked upon the silliest and most deluded ventures. Try re-reading C.S. Lewis's Screwtape Letters. Such fiction, unlike a lot of non-fiction these days, has the power to lead us closer to reality rather than further away from it. Lewis says that the notion of "humanity's search for the divine" strikes him a bit like talking about "the mouse's search for the cat"! I'm much more inclined to suspect Blaise Pascal is right when he says: "Men despise religion. They hate it and are afraid it may be true." The cure for this, of course, is a more careful and ongoing study of what true religion involves--how it is not contrary to reason, but worthy of reverence and respect. Worthy of reverence because it really understands human nature. Attractive because it promises true good.

One can feel as if God is smiling upon him when he is embarked upon the silliest and most deluded ventures. Try re-reading C.S. Lewis's Screwtape Letters. Such fiction, unlike a lot of non-fiction these days, has the power to lead us closer to reality rather than further away from it. Lewis says that the notion of "humanity's search for the divine" strikes him a bit like talking about "the mouse's search for the cat"! I'm much more inclined to suspect Blaise Pascal is right when he says: "Men despise religion. They hate it and are afraid it may be true." The cure for this, of course, is a more careful and ongoing study of what true religion involves--how it is not contrary to reason, but worthy of reverence and respect. Worthy of reverence because it really understands human nature. Attractive because it promises true good.

There is so much falsehood about Opus Dei floating around these days, particularly as a result of that marvellously engaging but satanically misleading book by Dan Brown,

There is so much falsehood about Opus Dei floating around these days, particularly as a result of that marvellously engaging but satanically misleading book by Dan Brown,  Third, we should meditate at least 15 minutes a day, by which I don't mean the mind-emptying form of meditation found in Zen Buddhism and other Eastern forms of mysticism, but rather a focusing of the mind upon Christ, an imaginative picturing of Him in some of the scenes the Gospels opens up for us, as well as upon aspects of our own relatedness to Him and to the saints. St. Josemaria Escriva, the founder of Opus Dei, used to hesitate briefly before passing through every door, because he would mentally allow his own guardian angel to pass through the door ahead of him-- not a bad excercise to remind us of the unseen reality all about us.

Third, we should meditate at least 15 minutes a day, by which I don't mean the mind-emptying form of meditation found in Zen Buddhism and other Eastern forms of mysticism, but rather a focusing of the mind upon Christ, an imaginative picturing of Him in some of the scenes the Gospels opens up for us, as well as upon aspects of our own relatedness to Him and to the saints. St. Josemaria Escriva, the founder of Opus Dei, used to hesitate briefly before passing through every door, because he would mentally allow his own guardian angel to pass through the door ahead of him-- not a bad excercise to remind us of the unseen reality all about us.

or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal.

or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal.  Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations--these are mortal,and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit-- immortal horrors or everlasting splendors. (C.S. Lewis,

Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations--these are mortal,and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit-- immortal horrors or everlasting splendors. (C.S. Lewis,  I think that's important too. Often our hunches represent intuitions that come from engrained habits of virtue. That's what allows the G.I. to throw himself on a grenade in a foxhole and save his buddies' lives at the cost of his own. He doesn't even have to think about it. It's instinctual.

I think that's important too. Often our hunches represent intuitions that come from engrained habits of virtue. That's what allows the G.I. to throw himself on a grenade in a foxhole and save his buddies' lives at the cost of his own. He doesn't even have to think about it. It's instinctual.

I've just purchased

I've just purchased  He's one of those authors who is not only a tremendous comfort, but offers some profound conceptual insights to back it up. You've probably seen Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger in the movie Shadowlands about his short-lived marriage to Joy Gresham, who already had cancer before they were married and died shortly afterwards. It's based on his posthumously published book, A Grief Observed.

He's one of those authors who is not only a tremendous comfort, but offers some profound conceptual insights to back it up. You've probably seen Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger in the movie Shadowlands about his short-lived marriage to Joy Gresham, who already had cancer before they were married and died shortly afterwards. It's based on his posthumously published book, A Grief Observed. you mentioned,

you mentioned,  There is a lot of reading about the female's experience of Catholicism that I find highly edifying-- for example,

There is a lot of reading about the female's experience of Catholicism that I find highly edifying-- for example,  St. Edith Stein's work,

St. Edith Stein's work,  "A parasite sucking out the living strength of another organism...the [housewife's] labor does not even tend toward the creation of anything durable.... [W]oman's work within the home [is] not directly useful to society, produces nothing. [The housewife] is subordinate, secondary, parasitic. It is for their common welfare that the situation must be altered by prohibiting marriage as a 'career' for woman." ~ Simone de Beauvoir,

"A parasite sucking out the living strength of another organism...the [housewife's] labor does not even tend toward the creation of anything durable.... [W]oman's work within the home [is] not directly useful to society, produces nothing. [The housewife] is subordinate, secondary, parasitic. It is for their common welfare that the situation must be altered by prohibiting marriage as a 'career' for woman." ~ Simone de Beauvoir,  Edith Stein (who wrote a dissertation

Edith Stein (who wrote a dissertation  under Husserl, before being martyred at Auschwitz), and still living philosophers such as John Crosby (left), Josef Seifert (right), Kenneth Schmitz , and others. A popularizer of the Pope's theology of the body is Christopher West, who has out a number of very good books I've recommended to my kids. Excellent, really; even revolutionary, in terms of overcoming the pervasive cultural drift, which is anything but healthy. [For more on this, check this

under Husserl, before being martyred at Auschwitz), and still living philosophers such as John Crosby (left), Josef Seifert (right), Kenneth Schmitz , and others. A popularizer of the Pope's theology of the body is Christopher West, who has out a number of very good books I've recommended to my kids. Excellent, really; even revolutionary, in terms of overcoming the pervasive cultural drift, which is anything but healthy. [For more on this, check this  But two things hold some help here: (1) the fact that there are often good souls in the precincts of the local church who can become wonderful spiritual friends, and, even more: (2) the knowledge that Christ is Himself there in His physical Body

But two things hold some help here: (1) the fact that there are often good souls in the precincts of the local church who can become wonderful spiritual friends, and, even more: (2) the knowledge that Christ is Himself there in His physical Body  and Blood to meet our battered souls amidst the braying asses (I'm thinking of contemporary music) of His stable. (By the way, you've read Thomas Day's wonderful book,

and Blood to meet our battered souls amidst the braying asses (I'm thinking of contemporary music) of His stable. (By the way, you've read Thomas Day's wonderful book,  First, as to whether Luther (pictured left) gets the credit he does on account of stumping for the Bible to be not only in the common language but also commonly available to those who were not priests and scholars. My guess is that Luther's translation was fairly shortly made available to all who could read and purchase ... perhaps the earlier editions had a more narrow circulation.

First, as to whether Luther (pictured left) gets the credit he does on account of stumping for the Bible to be not only in the common language but also commonly available to those who were not priests and scholars. My guess is that Luther's translation was fairly shortly made available to all who could read and purchase ... perhaps the earlier editions had a more narrow circulation.

Zwingli (pictured left) was not only a pugnacious opponent of Luther but a philanderer and adulterer, though I do not know whether it follows that on this account what he said about Luther here is false. My main point in this post was to offer a corrective to the wide-spread assumption that the Catholic Church tried to keep the laity biblically illiterate.

Zwingli (pictured left) was not only a pugnacious opponent of Luther but a philanderer and adulterer, though I do not know whether it follows that on this account what he said about Luther here is false. My main point in this post was to offer a corrective to the wide-spread assumption that the Catholic Church tried to keep the laity biblically illiterate.  The laity were virtually all illiterate for the fist sixteen centuries to begin with, but this hardly meant that they were ignorant of the Gospel. Eamon Duffy's

The laity were virtually all illiterate for the fist sixteen centuries to begin with, but this hardly meant that they were ignorant of the Gospel. Eamon Duffy's  Though it may not be quite "heresy," once can still see "de-Catholicizing" tendencies in many translations of Scripture today. To take just one example, there are thirteen instances of the term paradosis (usually in its plural form, paradoseis) in the NT, of which ten are critical of human traditions that have departed from God’s Word. In the other three cases, Paul commends traditions to the churches to whom he writes (1 Cor 11:2; 2 Thes 2:15; 3:6). Significantly all ten of the negative references are translated by the

Though it may not be quite "heresy," once can still see "de-Catholicizing" tendencies in many translations of Scripture today. To take just one example, there are thirteen instances of the term paradosis (usually in its plural form, paradoseis) in the NT, of which ten are critical of human traditions that have departed from God’s Word. In the other three cases, Paul commends traditions to the churches to whom he writes (1 Cor 11:2; 2 Thes 2:15; 3:6). Significantly all ten of the negative references are translated by the  A graduate student at the University of Glasgow currently working on his doctorate in patristics, my Jehovah's Witness friend, Edgar Foster, has been corresponding with me of late about

A graduate student at the University of Glasgow currently working on his doctorate in patristics, my Jehovah's Witness friend, Edgar Foster, has been corresponding with me of late about